Write Like a Thought Leader: Why No One Cares About Your Success Until You Do This (Russell Brunson’s Lesson)

Most people think audiences care about credentials.

They don’t.

They care about movement.

Russell Brunson understood this early. Long before ClickFunnels was a category, before the massive stages and seven-figure launches, he talked openly about what he was building, what was working, and what wasn’t, while it was still in motion.

That’s the lesson most aspiring thought leaders miss.

People don’t care about your success after it happens.

They care when they can see it unfolding.

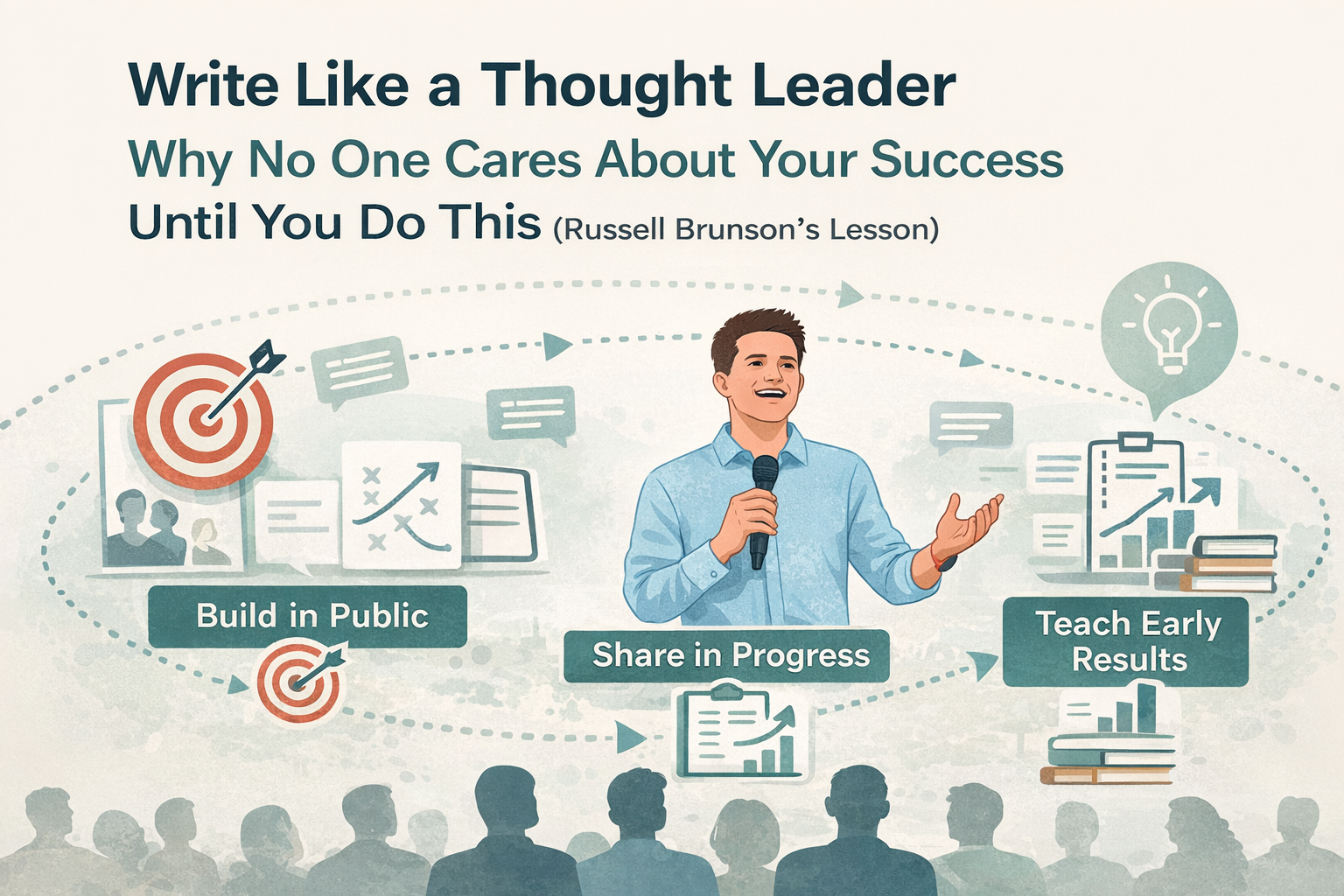

The Russell Brunson Pattern: Build in Public, Teach in Public

Russell Brunson doesn’t wait until something is “done” to talk about it.

He:

- shares frameworks as he’s using them

- teaches concepts while they’re being tested

- explains outcomes before they’re polished into case studies

This creates a powerful dynamic:

- audiences feel early

- trust builds faster

- momentum compounds

The key insight isn’t marketing bravado. It’s psychology.

People don’t attach to finished success.

They attach to visible commitment.

The Principle: People Care When You Take Yourself Seriously

Here’s the core thought leadership principle behind this post:

People don’t validate your success. They respond to your conviction.

Russell didn’t wait for the world to crown him credible.

He acted like the work mattered before anyone else did.

That posture, repeated publicly, creates gravity.

Why This Matters for Authors

Most nonfiction authors do the opposite.

They:

- hide until the book is “good enough”

- wait for permission to teach

- assume attention comes after achievement

But attention is built before the book is finished.

Russell’s style proves a counterintuitive truth:

Teaching is how you earn the right to be followed.

The “Conviction-First” Writing Framework

This is how to apply the Russell Brunson lesson directly to your book and content.

1) Lead with belief, not validation

Start chapters and posts by stating what you believe now, not what you’ve proven forever.

Example:

“Most funnels fail because people overbuild before they understand demand.”

That sentence doesn’t require universal proof. It requires ownership.

Why it works:

Belief signals leadership. Hedging signals insecurity.

2) Teach from the middle, not the finish line

Russell teaches while building, not after the case study is complete.

As an author, that means:

- write from the testing phase

- share partial results

- explain what you’re trying and why

This doesn’t weaken authority. It humanizes it.

Why it works:

Readers trust people who are in the arena, not just reporting from it.

3) Show progress, not perfection

You don’t need a massive win to earn attention.

You need:

- a direction

- momentum

- consistency

Russell constantly shows:

- iterations

- refinements

- new versions of old ideas

Why it works:

Progress feels real. Perfection feels distant.

4) Name the pattern you’re discovering

The shift from “story” to “thought leadership” happens here.

After sharing what you’re doing, extract the insight:

- What’s working?

- What keeps repeating?

- What surprised you?

This turns activity into teaching.

Example:

“Every time we simplified the message, conversion improved. Complexity was the enemy.”

Now it’s not just a story. It’s a principle.

5) Invite the reader to act alongside you

Russell’s work often feels collaborative, not declarative.

End sections with:

- “Try this”

- “Test this”

- “Watch what happens when you…”

This frames the reader as a participant, not a spectator.

How This Shows Up in Manuscripts Projects

The authors who gain traction fastest don’t wait to feel “successful.”

They:

- put "Working Title (Coming 2026" in their LinkedIn bio before they've finished their first draft

- publish while learning

- teach before the book is finished

- share frameworks as living tools

Their books feel alive because they were shaped in public.

This mirrors the Russell Brunson model exactly.

Evidence That This Works

1) Pattern Evidence

Audiences consistently engage more with in-progress insights than polished retrospectives.

2) Social Evidence

Readers frequently say:

“I feel like I’m learning alongside you.”

That’s not accidental. That’s design.

3) Outcome Evidence

Authors who teach early:

- build audiences faster

- get better feedback

- write stronger books because ideas are pressure-tested

Common Mistakes (and Fixes)

Mistake: Waiting to be “successful enough”

Fix: Act like the work matters now

Mistake: Over-explaining credentials

Fix: Demonstrate belief through consistent action

Mistake: Hiding drafts and ideas

Fix: Share thinking before it’s perfect

A Simple Template You Can Copy

Use this when drafting a chapter or post:

- Belief: “Here’s what I think is true right now.”

- Action: “Here’s what I’m doing to test it.”

- Observation: “Here’s what I’m seeing so far.”

- Pattern: “Here’s the principle emerging.”

- Invitation: “Here’s how you can try this.”

This is conviction made visible.

Quick FAQ

Why don’t people care about my success yet?

Because they can’t see your commitment in motion. Visibility precedes validation.

What did Russell Brunson do differently?

He taught while building, shared frameworks early, and acted like the work mattered before it was widely successful.

Is this the same as “building in public”?

Related, but more intentional. This is teaching in public, not just sharing updates.

The Bottom Line

People don’t rally behind finished success.

They rally behind belief, motion, and leadership.

Russell Brunson didn’t wait to be impressive.

He showed up convinced.

If you want to write like a thought leader, start there.

→ Schedule Your Free Strategy Call

About the Author

Eric Koester is an award-winning entrepreneurship professor at Georgetown University, bestselling author, and founder of Manuscripts, the Modern Author OS used by more than 3,000 authors. His work has helped creators turn ideas into books, books into brands, and brands into scalable businesses.

About Manuscripts

Manuscripts is the leading full-service publishing partner for modern nonfiction authors. We help founders, executives, coaches, and experts turn their books into growth engines, through positioning, coaching, developmental editing, design, AI-enhanced writing tools, and strategic launch systems. Manuscripts authors have sold thousands of books, booked paid speaking gigs, landed media features, and generated millions in business from their IP.

Work With Us

If you’re writing a book you want to matter, let’s map out your Modern Author Plan.

👉 Schedule a Modern Author Strategy Session → https://write.manuscripts.com/maa-web

👉 Explore Manuscripts Publishing Services → https://manuscripts.com/publish-with-us/

👉 See Modern Author Success Stories → https://manuscripts.com/authors/

Modern Author Resources

- How to Write a Book if You’re Busy

- Modern Ghostwriting for Nonfiction Authors

- AI Tools for Authors in 2026

- How to Build an Audience Before You Write Your Book

- The Evergreen Launch System for Modern Authors

Powered by Codex: The Modern Author Author Intelligence Tool