Self-Editing Tips for Beginning Writers

So, you’re just starting your new book and you’re new to this whole ‘writing’ thing. Or maybe you’re a seasoned writer who has written blogs, articles, or fiction. However you came to this current manuscript, the following advice can help you, even if it’s a reminder.

There are two main areas of editing to think about: spelling and grammar.

John Palisano’s nonfiction, short fiction, and poetry have appeared in countless literary anthologies and magazines such as Cemetery Dance, Fangoria, Weird Tales, Space & Time, McFarland Press, and many more. He is the author of the novel Nerves and Starlight Drive: Four Tales of Halloween, and has been quoted in Vanity Fair, the Los Angeles Times, and The Writer. He has received the Bram Stoker Award© and was recently President of the Horror Writers Association. Say ‘hi’ at: johnpalisano.com, amazon.com/author/johnpalisano, facebook.com/johnpalisano, and twitter.com/johnpalisano

Spelling

This one’s easy, right? Microsoft Word, Google Docs, Scrivener . . . all the big ones have spell check built right in. On top of that? There are services such as Grammarly and ProWritingAid that do a pretty good job of catching the biggest, most egregious mistakes. As far as each of these tools has come (Does anyone remember the early days of spell check where the suggested spelling was more often than not completely wrong?) they still need an actual human being to make sure they’re getting everything correct. Consider self-driving cars. There’s a lot they can do now (other than catch on fire randomly) but for now and in the near future, a human driver is required behind the wheel. Well, you’re going to need to be that human driver behind the wheel of your manuscript when you employ those great digital tools. Here’s a big rule: it is not enough to rely solely on built-in or third-party spell checkers. Reading your manuscript carefully catches errors in addition to what the computers will find. You’ll likely find missing words, misused words, and any other number of things that need fixing. Another benefit of doing a spelling pass is that you will more than likely fine-tune other aspects of the work you may have missed while feverishly writing your drafts. Another caveat? It’s ideal to have another person do a pass, as well. Our minds tend to ‘fix’ things automatically. We hear words in our own voices. It can be a challenge to find everything. I didn’t believe this for years until I became a professional copy editor. My work would come back with errors that I couldn’t believe. How could I miss some of these very basic things? My answer was that my mind was doing the auto-correct thing. Strange, but true. I’ve spoken to other editors who deal with the same phenomena. That being said, you can eliminate a ton of these errors with the methods outlined above. It will go a long way to making life a lot easier for your copy editors later.Grammar

This is a much more complex type of editing. Think of grammar as the blueprint or architecture of writing. What parts make up a sentence? See Jane run. Grammar can be very simple, or very complex, of course. This is where things can get very tricky, especially for the auto-corrects and yes . . . even Grammarly, despite its name. English is a very challenging language. Again, these tools can help guide you, but they are even less effective than their use for correcting spelling mistakes. The biggest issue I’ve seen with grammar has to do with tense and point of view. When correcting your manuscript, make sure your verb tenses are the same throughout a section or chapter. Example: if you begin a section using past tense; ‘John liked writing stories’; stick to those verb tenses. In this case, you’d primarily use verbs ending in ‘-ed’. Switching to the present tense, such as, ‘John edits the stories he’s writing’ presents a tense conflict and needs to be addressed. Now, let’s say you want to switch tenses. If you must, use a section break (***) to do so, signaling your reader of the change. And make sure to add another section break when you’re switching back, too. Although, this style isn’t common for current fiction readers.Point of View

This is another big issue, mainly in fiction writing. It boils down to character perspective. If it’s the main character’s point of view, stay there. Don’t ‘hop’ into another character’s head in the middle of the scene. Head-hopping is jarring and hard to follow. You want to stick with one point of view (POV) during your entire section or chapter. If you do want to ‘hop heads’, use a section break (***), and make sure to close the section with one, too, if you switch back. In popular, commercial writing, be aware that sticking to one POV per section or chapter is much preferred by agents, publishers, and especially your readers. This wasn’t always the case. In many gothic texts, and even up through the mid-20th century, head-hopping and even dialogue were often crammed into one paragraph. Sticking to one POV per chapter is something major to look out for when redrafting and editing your manuscript.Learn More

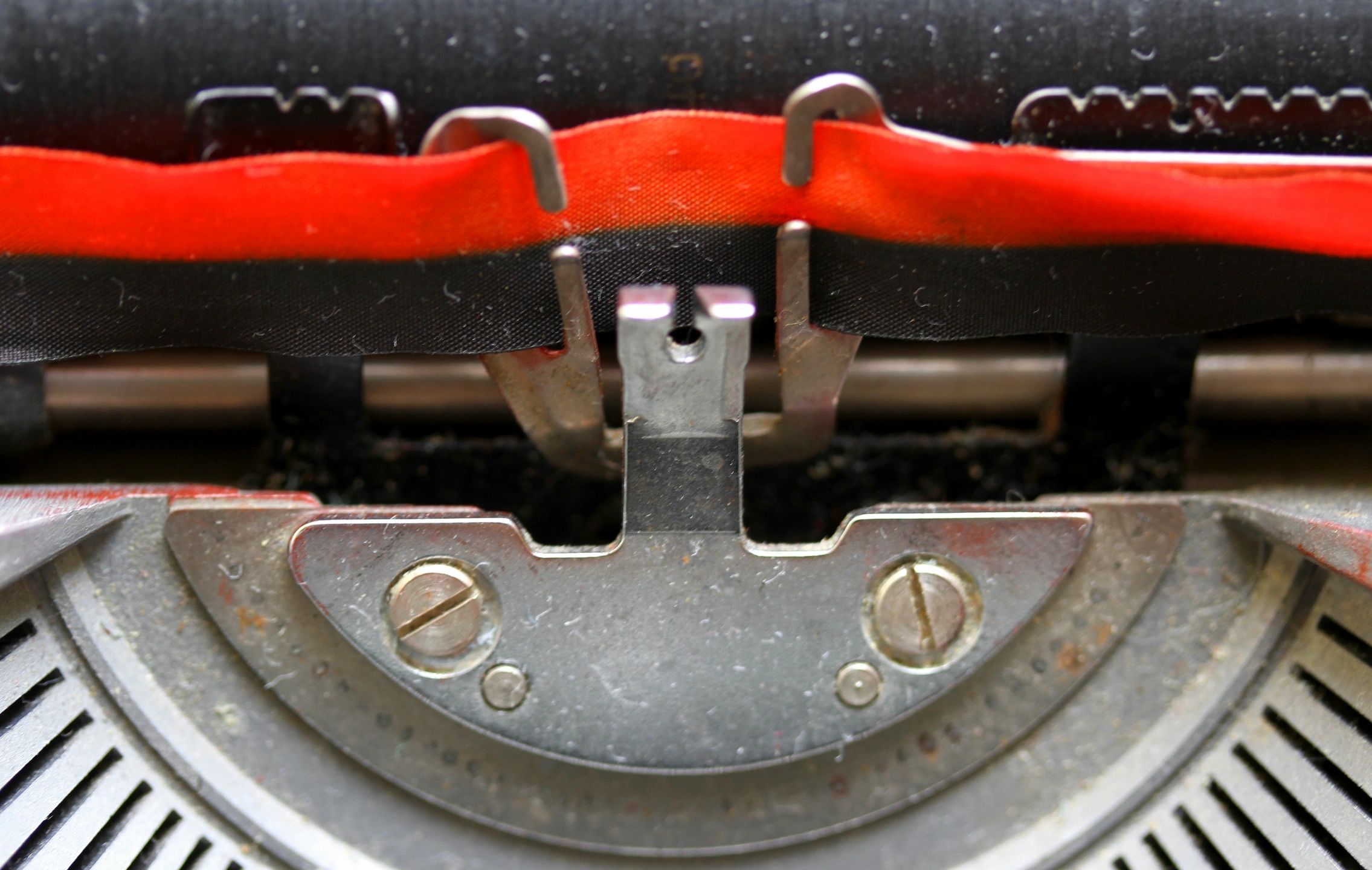

One of the first lines of defense is to school yourself in these matters! It’s not very time-consuming and it will serve you well. My highest recommendation is reading Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style. It is a thin book, under 100 pages. Inside, it has almost everything you need to know to write clearly, concisely, and professionally. I read it annually as a refresher. Another great book to check out is Self-Editing for Fiction Writers by Dave King and Renni Brown. This is a much more extensive and detailed book, but the tools and advice are priceless.Online

There are some amazing sites you can check out, as well. The major dictionary, thesaurus, and encyclopedia brands all have excellent, and in most cases, free pages with convenient search tools. One of my favorite sites is Grammar Girl’s Quick and Dirty Tricks https://www.quickanddirtytips.com/grammar-girl/ if you really want to do a deep dive, it’s also a great resource for searching those peculiar grammatical pickles in which we sometimes find ourselves. Happy writing and happy editing!John Palisano’s nonfiction, short fiction, and poetry have appeared in countless literary anthologies and magazines such as Cemetery Dance, Fangoria, Weird Tales, Space & Time, McFarland Press, and many more. He is the author of the novel Nerves and Starlight Drive: Four Tales of Halloween, and has been quoted in Vanity Fair, the Los Angeles Times, and The Writer. He has received the Bram Stoker Award© and was recently President of the Horror Writers Association. Say ‘hi’ at: johnpalisano.com, amazon.com/author/johnpalisano, facebook.com/johnpalisano, and twitter.com/johnpalisano