How to Write Like a Thought Leader: The James Clear Principles Framework for Nonfiction Authors

Great Books Aren’t Written — They’re Structured

Most first-time authors start with the wrong question:

“How do I write a great chapter?”

The better question:

“How do I structure my ideas so readers understand, remember, and act on them?”

Thought leaders don’t win because they’re better writers.

They win because their ideas are delivered through a structure that makes those ideas unavoidable.

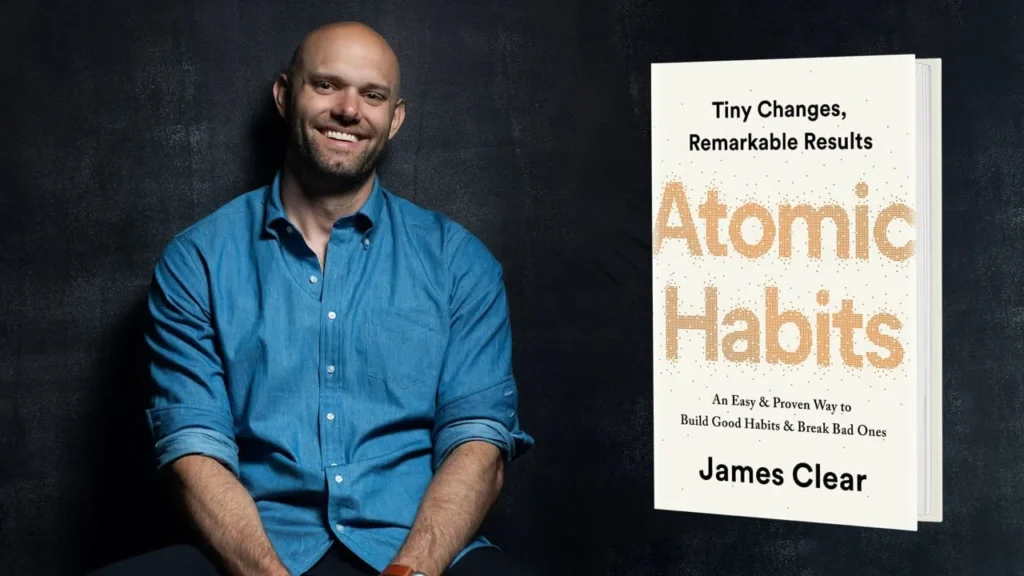

And James Clear’s Atomic Habits provides one of the cleanest, most repeatable structures modern authors can steal.

At Manuscripts, we’ve studied more than 2,500 nonfiction books inside the Modern Author OS. Across industries, voices, and genres, one pattern keeps showing up:

Readers trust frameworks more than opinions.

Readers remember stories more than arguments.

Readers act when structure makes action simple.

James Clear mastered that blend.

In this guide, you’ll learn exactly how to use Clear’s “Principles Framework” to build chapters that feel polished, persuasive, and inevitable — even if you’re busy, overwhelmed, or unsure how to organize your ideas.

This is the approach we use inside the Modern Author Accelerator and Codex AI to help authors transform scattered expertise into clean, compelling chapters.

Why Readers Trust Principles More Than Advice

Most books fail because they tell people what to do instead of showing how the world works.

Advice feels personal.

Principles feel universal.

James Clear built his book around principles like:

- Identity drives habits

- Environment shapes behavior

- Small improvements compound

These aren’t tips.

These are truths.

A principle is a timeless rule about how something works.

When a reader recognizes it, you get instant credibility.

Why Principles Work So Well in Modern Thought Leadership

They:

- Create shared language

- Anchor your frameworks

- Make your ideas portable

- Encourage word-of-mouth (“She teaches the principle of X…”)

- Position you as a category thinker, not an advice-giver

If you want to write like a thought leader, your chapters must translate your expertise into principles — then prove them with stories, data, and frameworks.

The James Clear Chapter Structure (Reverse Engineered)

We broke down Clear’s chapters across Atomic Habits and found a repeatable flow:

THE CLEAR PRINCIPLES CHAPTER MODEL

- Start With a Story A vivid, often surprising story that represents the principle in action.

- State the Principle A clear, memorable truth about how the world works.

- Explain the Principle Why does this principle matter? What makes it universal?

- Demonstrate the Principle Real-world examples, research, case studies, or analogies.

- Introduce a Framework A simple, visualizable system or model that operationalizes the principle.

- Apply the Framework Show readers what to do and how to do it.

- End With a Memorable Line or Punchline A repeatable idea that readers can’t forget.

This structure is extremely friendly for:

- Busy authors

- Business leaders

- Consultants

- Coaches

- Creators

- Anyone trying to turn expertise into IP

It reduces blank-page stress and gives your reader cognitive grip.

Build Your Chapter Around One Core Principle

Every great chapter answers one question:

“What is the single principle this chapter proves?”

If your chapter has three ideas, it’s confusing.

If it has one idea, it’s powerful.

Your principle must be:

- True (backed by research or lived experience)

- Simple (plain language)

- Useful (changes behavior or perspective)

- Memorable (easy to teach)

Examples:

- “People don’t rise to the level of their goals. They fall to the level of their systems.”

- “Clarity creates courage.”

- “Positioning is what you own in the mind, not what you say in the pitch.”

Inside Codex, this is where we extract:

- Repeated beliefs

- Thematic patterns

- Contrasts

- Identity statements

- Core insights

And then synthesize them into a clean principle.

Start With a Story (Your Anchor)

Clear opens nearly every chapter with a surprising or emotional story.

Why?

Because stories create cognitive hooks.

The story makes the principle stick.

Your story must do at least one of these:

- Illustrate the principle in action

- Represent a transformation

- Set up the problem the reader is facing

- Create tension or curiosity

- Build trust through vulnerability

Examples from Clear:

- The British cycling team transformation

- The Japanese train station cleaning ritual

- The Seinfeld chain method

Stories = stickiness.

Principles = clarity.

Frameworks = action.

That combination creates bestseller energy.

Demonstrate the Principle With Multiple Angles

James Clear doesn’t just state a principle and move on.

He proves it three ways:

1. Research or data

Gives credibility.

2. Examples or case studies

Makes it relatable.

3. Metaphors or analogies

Makes it memorable.

When we work with authors, we call this the Evidence Bundle.

One principle → three types of proof.

This is where the Manuscripts methodology shines:

we teach authors how to gather stories, turn them into data, and feed them into Codex so that each chapter writes itself.

Turn Your Principle Into a Framework

This is where most first-time authors fall short.

They give great stories.

They explain great ideas.

They forget to give readers a system.

James Clear always does.

He turns principles into:

- 4 Laws

- Systems

- Rules

- Models

- Step-by-step processes

A framework moves readers from “I understand” to “I can use this.”

For your book:

- Give every chapter one framework

- Make it visual

- Use 3–5 steps (cognitively optimal)

- Tie each step back to the principle

This is also how you turn your book into:

- A keynote talk

- A workshop

- A course

- A coaching program

- An enterprise training system

Frameworks = monetization.

Close With a Punchline or Insight They Can’t Forget

Clear ends each chapter with a sharp, memorable line.

These lines often end up:

- Quoted

- Shared

- Highlighted

- Used in talks

- Referenced in articles

Examples:

- “You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.”

- “Every action you take is a vote for the type of person you wish to become.”

Your closing line should be:

- Short

- True

- Repeatable

- Aligned with the principle

This becomes your intellectual signature.

Your Chapter Template (Manuscripts Version)

Here’s the Manuscripts + James Clear hybrid chapter template:

CHAPTER TITLE (Benefit + Insight)

1. Opening Story

One vivid, emotional story that sets up the idea.

2. State the Core Principle

One sentence.

3. Explain the Principle

Why it matters. Why it’s universal.

4. Demonstrate the Principle

- Research

- Case studies

- Examples

- Metaphors

5. Introduce the Framework

3–5 steps.

6. Apply the Framework

Practical, step-by-step implementation.

7. Close With a Punchline

One memorable, tweet-length idea.

Feed this to Codex and you’ll get a chapter preview in 20 seconds.

Why This Structure Works for Busy Authors

If you’re a busy modern author, you need structure that creates speed.

This model gives you:

- A predictable chapter flow

- A way to write in 60–90 minute bursts

- A framework that turns scattered notes into clear structure

- A repeatable process you can use 10–12 times

- A blueprint for repurposing every chapter into content

This is why our Accelerator authors can write high-quality drafts in 8–14 weeks even with full-time jobs.

How Codex Accelerates This Entire Process

Codex turns the James Clear method into an automated outline generator.

Upload a transcript, notes, or a research dump and Codex will:

- Extract potential principles

- Map your stories to principles

- Identify gaps

- Cluster examples

- Propose 3–5 frameworks

- Generate chapter outlines

- Rewrite principles in cleaner language

- Produce chapter summaries, headlines, and social posts

This takes authors from overwhelm to momentum fast.

Bringing It All Together

Writing like a thought leader is not about being a genius.

It’s about having a structure that elevates your ideas.

James Clear gave modern authors one of the most effective chapter models in nonfiction.

Use it.

Adapt it.

Make it your own.

This framework, combined with Codex and the Modern Author OS, gives you everything you need to write chapters that are clear, persuasive, memorable, and actionable.

If you want to write like a thought leader, build chapters around principles.

Principles build books.

Books build opportunities.

Opportunities build a platform.

Call to Action

If you want help using the James Clear Principles Framework to write your book, schedule a free strategy call with Manuscripts.

We’ll help you:

- Identify your core principles

- Build your frameworks

- Structure your chapters

- Use Codex to accelerate your draft

- Build your platform while writing

- Turn your book into speaking, clients, and business growth

→ Schedule Your Free Strategy Call

About the Author

Eric Koester is an award-winning entrepreneurship professor at Georgetown University, bestselling author, and founder of Manuscripts, the Modern Author OS used by more than 3,000 authors. His work has helped creators turn ideas into books, books into brands, and brands into scalable businesses.

About Manuscripts

Manuscripts is the leading full-service publishing partner for modern nonfiction authors. We help founders, executives, coaches, and experts turn their books into growth engines, through positioning, coaching, developmental editing, design, AI-enhanced writing tools, and strategic launch systems. Manuscripts authors have sold thousands of books, booked paid speaking gigs, landed media features, and generated millions in business from their IP.

Work With Us

If you’re writing a book you want to matter, let’s map out your Modern Author Plan.

👉 Schedule a Modern Author Strategy Session → https://write.manuscripts.com/maa-web

👉 Explore Manuscripts Publishing Services → https://manuscripts.com/publish-with-us/

👉 See Modern Author Success Stories → https://manuscripts.com/authors/

Modern Author Resources

- How to Write a Book if You’re Busy

- Modern Ghostwriting for Nonfiction Authors

- AI Tools for Authors in 2026

- How to Build an Audience Before You Write Your Book

- The Evergreen Launch System for Modern Authors

Powered by Codex: The Modern Author AI Tool